Artículos relacionados a The Pregnant Widow

Where We Lay Our Scene

1

Franca Viola

It was the summer of 1970, and time had not yet trampled them flat, these lines:

Sexual intercourse began

In 1963

(Which was rather late for me)—

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

—Philip Larkin, “Annus Mirabilis” (formerly “History”), Cover magazine, February 1968

But now it was the summer of 1970, and sexual intercourse was well advanced. Sexual intercourse had come a long way, and was much on everyone’s mind.

Sexual intercourse, I should point out, has two unique characteristics. It is indescribable. And it peoples the world. We shouldn’t find it surprising, then, that it is much on everyone’s mind.

Keith would be staying, for the duration of this hot, endless, and erotically decisive summer, in a castle on a mountainside above a village in Campania, in Italy. And now he walked the backstreets of Montale, from car to bar, at dusk, flanked by two twenty-year-old blondes, Lily and Scheherazade . . . Lily: 5' 5", 34-25-34. Scheherazade: 5' 10", 37-23-33. And Keith? Well, he was the same age, and slender (and dark, with a very misleading chin, stubbled, stubborn-looking); and he occupied that much-disputed territory between five foot six and five foot seven.

Vital statistics. The phrase originally referred, in studies of society, to births and marriages and deaths; now it meant bust, waist, hips. In the long days and nights of his early adolescence, Keith showed an abnormal interest in vital statistics; and he used to dream them up for his solitary amusement. Although he could never draw (he was all thumbs with a crayon), he could commit figures to paper, women in outline, rendered numerically. And every possible combination, or at least anything remotely humanoid—35-45-55, for instance, or 60-60-60—seemed well worth thinking about. 46-47-31, 31-47-46: well worth thinking about. But you were always tugged back, somehow, to the archetype of the hourglass, and once you’d run up against (for instance) 97-3-97, there was nowhere new to go; for a contented hour you might stare at the figure eight, upright, and then on its side; until you drowsily resumed your tearful and tender combinations of the thirties, the twenties, the thirties. Mere digits, mere integers. Still, when he was a boy, and he saw vital statistics under the photograph of a singer or a starlet, they seemed garrulously indiscreet, telling him everything he needed to know about what was soon to be. He didn’t want to hug and kiss these women, not yet. He wanted to rescue them. From an island fortress (say) he would rescue them . . .

34-25-34 (Lily), 37-23-33 (Scheherazade)—and Keith. They were all at the University of London, these three; Law, Mathematics, English Literature. Intelligentsia, nobility, proletariat. Lily, Scheherazade, Keith Nearing.

They walked down steep alleyways, scooter-torn and transected by wind-ruffled tapestries of clothing and bedding, and on every other corner there lurked a little shrine, with candles and doilies and the lifesize effigy of a saint, a martyr, a haggard cleric. Crucifixes, vestments, wax apples green or cankered. And then there was the smell, sour wine, cigarette smoke, cooked cabbage, drains, lancingly sweet cologne, and also the tang of fever. The trio came to a polite halt as a stately brown rat—lavishly assimilated—went ambling across their path: given the power of speech, this rat would have grunted out a perfunctory buona sera. Dogs barked. Keith breathed deep, he drank deep of the ticklish, the teasing tang of fever.

He stumbled and then steadied. What was it? Ever since his arrival, four days ago, Keith had been living in a painting, and now he was stepping out of it. With its cadmium reds, its cobalt sapphires, its strontian yellows (all freshly ground), Italy was a painting, and now he was stepping out of it and into something he knew: downtown, and the showcase precincts of the humble industrial city. Keith knew cities. He knew humble high streets. Cinema, pharmacy, tobacconist, confectioner. With expanses of glass and neon-lit interiors—the very earliest semblances of the boutique sheen of the market state. In the window there, mannequins of caramelised brown plastic, one of them armless, one of them headless, arranged in attitudes of polite introduction, as if bidding you welcome to the female form. So the historical challenge was bluntly stated. The wooden Madonnas on the alleyway corners would eventually be usurped by the plastic ladies of modernity.

Now something happened—something he had never seen before. After fifteen or twenty seconds, Lily and Scheherazade (with Keith somehow bracketed in the middle of it) were swiftly and surreally engulfed by a swarm of young men, not boys or youths, but young men in sharp shirts and pressed slacks, whooping, pleading, cackling—and all aflicker, like a telekinetic card trick of kings and knaves, shuffling and riffling and fanning out under the streetlamps . . . The energy coming off them was on the level (he imagined) of an East Asian or sub-Saharan prison riot—but they didn’t actually touch, they didn’t actually impede; and after a hundred yards they fell like noisy soldiery into loose formation, a dozen or so contenting themselves with the view from the rear, another dozen veering in from either side, and the vast majority up ahead and walking backward. And when do you ever see that? A crowd of men, walking backward?

Whittaker was waiting for them, with his drink (and the mailsack), on the other side of the smeared glass.

Keith went on within, while the girls lingered by the door (conferring or regrouping), and said,

“Was I seeing things? That was a new experience. Jesus Christ, what’s the matter with them?”

“It’s a different approach,” drawled Whittaker. “They’re not like you. They don’t believe in playing it cool.”

“I don’t either. I don’t play it cool. No one’d notice. Play what cool?”

“Then do what they do. Next time you see a girl you like, do a jumping jack at her.”

“It was incredible, that. These—these fucking Italians.”

“Italians? Come on, you’re a Brit. You can do better than Italians.”

“Okay, these wogs—I mean wops. These fucking beaners.”

“Beaners are Mexicans. This is pathetic. Italians, Keith—spicks, greaseballs, dagos.”

“Ah, but I was raised not to make distinctions based on race or culture.”

“That’ll be a lot of help to you. On your first trip to Italy.”

“And all those shrines . . . Anyway, I told you, it’s my origins. Me, I don’t judge. I can’t. That’s why you’ve got to look out for me.”

“You’re susceptible. Your hands shake—look at them. And it’s hard work being a neurotic.”

“It’s more than that. I’m not nuts, exactly, but I get episodes. I don’t see things clearly. I misread things.”

“Particularly with girls.”

“Particularly with girls. And I’m outnumbered. I’m a bloke and a Brit.”

“And a het.”

“And a het. Where’s my brother? You’ll have to be a brother to me. No. Treat me as the child you never had.”

“Okay, I will. Now listen. Now listen, son. Start looking at these guys with a bit of perspective. Johnny Eyetie is a play-actor. Italians are fantasists. Reality’s not good enough for them.”

“Isn’t it? Not even this reality?”

They turned, Keith in his T-shirt and jeans, Whittaker in his horn-rims, the oval leather elbow-patches on his cord jacket, the woollen scarf, fawn, like his hair. Lily and Scheherazade were now making their way towards the stairs to the basement, eliciting, from the elderly all-male clientele, a fantastic diversity of scowls; their soft shapes moved on, through the gauntlet of gargoyles, then swivelled, then exited downward, side by side. Keith said,

“Those old wrecks. What are they looking at?”

“What are they looking at? What do you think they’re looking at? Two girls who forgot to put any clothes on. I said to Scheherazade, You’re going to town tonight. Put some clothes on. Wear clothes. But she forgot.”

“Lily too. No clothes.”

“You don’t make cultural distinctions. Keith, you should. These old guys have just come staggering out of the Middle Ages. Think. Imagine. You’re first-generation urban. With your wheelbarrow parked in the street. You’re having a little glass of something, trying to keep a grip. You look up and what do you get? Two nude blondes.”

“. . . Oh, Whittaker. It was so horrible. Out there. And not for the obvious reason.”

“What’s the non-obvious reason?”

“Shit. Men are so cruel. I can’t say it. You’ll see for yourself on the way back . . . Look! They’re still there!”

The young men of Montale were now on the other side of the window, stacked like silent acrobats, and a jigsaw of faces squirmed against the glass—strangely noble, priestlike faces, nobly suffering. One by one they started dropping back and peeling away. Whittaker said,

“What I don’t get is why the boys don’t act like that when I walk down the street. Why don’t the girls do jumping jacks when you walk down the street?”

“Yeah. Why don’t they?”

Four jars of beer were slewed out in front of them. Keith lit a Disque...

'Read it: it is hilarious, wonderfully perceptive, uncompromisingly ambitious and written by a great master of the English language'

Justin Cartwright, FINANCIAL TIMES

'Moving and humane, The Pregnant Widow also captivates by the accustomed wit and elegance of its style. It is beautifully achieved, cunningly relaxed, and reveals considerable emotional depth'

Philip Hensher, DAILY TELEGRAPH

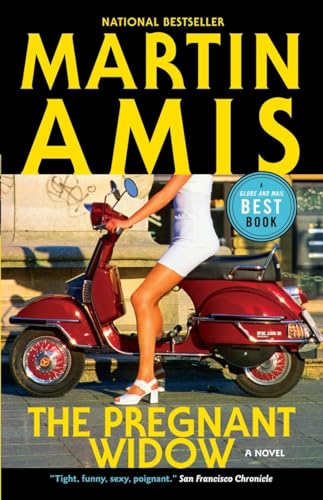

An Italian castle, Summer, 1970. Sex is very much on everyone's mind. The girls are acting like boys and the boys are going on acting like boys. Keith Nearing - a bookish twenty year old, in that much disputed territory between five foot six and five foot seven - is struggling to twist feminism towards his own ends. Torn between three women, his scheming doesn't come off quite as he expects.

And now in the twenty first century, as he reflects on that summer holiday, the aftershocks of the sexual revolution finally catch up with Keith Nearing.

The Pregnant Widow is gloriously risqué and ferociously funny. It is Martin Amis at his fearless best.

'No one better understands the cosmic joke that is humanity. Nor is anyone as funny telling it' OBSERVER

'Amis writes thrillingly well... It is funny, clever and knowing'

DAILY MAIL

'Delight us Amis does, and as few can'

INDEPENDENT

'What a voice! There's a full-throated energy to this book that makes more respectable contemporary novels look like turgid waffle'

GUARDIAN

"Sobre este título" puede pertenecer a otra edición de este libro.

- ISBN 10 0676977820

- ISBN 13 9780676977820

- EncuadernaciónBroché

- Número de páginas288

- Valoración

Gastos de envío:

EUR 9,21

De Canada a Estados Unidos de America

Los mejores resultados en AbeBooks

The Pregnant Widow

Descripción Paperback. Condición: Good. Nº de ref. del artículo: FORT781825

The Pregnant Widow

Descripción Paperback. Condición: Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.7. Nº de ref. del artículo: G0676977820I5N00